Scientists have discovered that scanning the brains of potential service dogs can help identify those dogs which would ultimately fail service dog training.

People now may be able to better determine the good (and not so good) canine candidates for service dog training using Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging technology.

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) method measures brain activity by detecting where blood is flowing to the brain, and therefore which parts of the brain are activated when in use.

A study conducted by Prof. Gregory Berns, MD, PhD at Emory University has found that using fMRIs to determine potential success of service training in dogs has increased the ability to find potential training failures by about 20 percent.

Greg Berns is most well-known for his fMRI work with dogs that expanded our understanding of the dog's brain and cognition, and his book How Dogs Love Us.

Details of the study

The study, published in Scientific Reports, involved 43 dogs who went through service training at Canine Companions for Independence (CCI) in Santa Rosa, California.

According to Gregory Berns, who led the research, the brain scans not only told them which dogs were more likely to fail, but why.

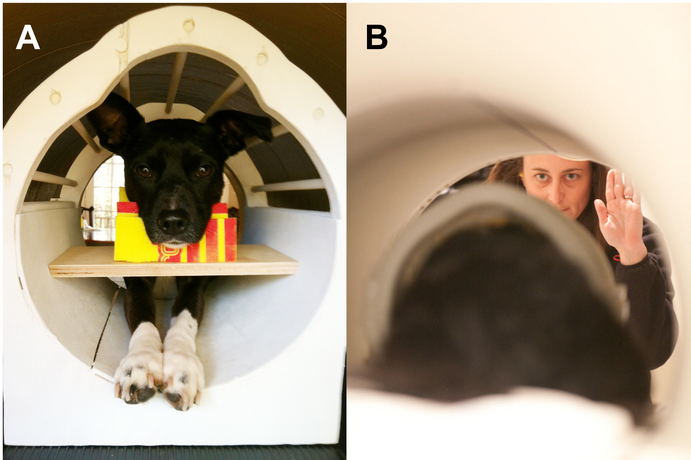

Photo: Gregory Berns, Emory University

Before even being selected for service training, each dog underwent an array of behavioral testing to prove that they had the right temperament for the job.

The fMRIs helped shed light on a trend; though each dog had a calm exterior, the ones who showed higher activity in the amygdala (the region associated with excitability) were ultimately more likely to fail service training.

For the study, potential service dogs were first taught how to remain motionless while undergoing an MRI. The Berns lab was the first one to test conscious, unrestrained dogs. This was part of an overall effort to understand canine cognition and interspecies communication.

The experiments basically focused on using hand signals to indicate whether or not a dog would receive a treat, and used different people to give the signals. Dogs’ brain activity was measured for each scenario.

The study focused on two regions of the brain: the amygdala and the caudate. The caudate region is associated with reward in humans.

This reward region is the one which became activated when the dogs were shown the hand signal for “treat.” It did not become activated when they were shown the signal for “no treat.”

Sometimes the signals were given by the dog’s trainer, and sometimes they were given by a stranger. Dogs showing more activity in the caudate (reward) region of the brain in response to the “treat” signal – regardless of who gave the signal – were more likely to be successful in their training.

Dogs showing more activity in the excitability (amygdala) region of the brain in response to this signal – particularly if this signal was given by a stranger – were more likely to fail their service training.

RELATED: How to Get a Service Dog for Anxiety or Depression

Impact of this study's findings

Canines who will be trained to assist people with disabilities undergo intense service training programs, and it can cost upwards of $50,000 to train one dog.

As many as 70 percent of dogs who begin service training eventually flunk out due to behavior. Training programs typically ensure for 6-9 months

Identifying those dogs which may fail the training will save trainers a significant amount of time and money. There are long waiting lists for service dogs; weeding out the potential failures could speed up the process and get people service dogs faster.

Because of the cost of an MRI, this approach will not be feasible for individual trainers. But it will be practical and useful for those organizations which train many dogs every single year.

RELATED: Does My Dog Love Me? Myths and Facts About Dog Emotions

In conclusion

Ideal service dogs are those which are highly motivated, but not excessively excitable or nervous. The focus on the caudate vs. amygdala regions of brain activity seems to have helped researchers better determine which dogs were highly motivated vs. which dogs were highly excitable.

Now, according to the researchers, we may be better equipped to detect variations in dogs’ mental states before those variations are able to manifest less ideal behaviors.

Berns hopes to see this technology and his team’s research lend application to broader areas of working dogs, such as military assistance dogs and K-9 police dogs.

Looking further ahead and more broadly, perhaps studies and research like this may also help humans to better understand canine behavior and motivation, and to therefore improve upon training methods for the more basic functions of dog ownership.

If we can better understand what motivates, excites, and discourages our canine companions, we can work better with them to ensure ideal dynamics between man and dog.

With enough time and scientific discovery, humans can better choose their ideal canine companions – people with kids can avoid choosing a dog which may be stressed out by children. People with physical limitations can better choose a dog who will comply with their lifestyle.

If you understand what’s going on in your dog’s mind, it can help both you and the dog avoid stressful situations, and exist more happily together in a complicated world.

Reference:

- Gregory S. Berns, Andrew M. Brooks, Mark Spivak, Kerinne Levy. Functional MRI in Awake Dogs Predicts Suitability for Assistance Work. Scientific Reports, 2017; 7: 43704 DOI: 10.1038/srep43704