A new study found that mating dogs and wolves over the last few hundred years has forever changed the wolf's gene pool.

Let me tell you a quick and relevant story first. A friend of mine has four Siberian huskies. Not one, not two, but four. She also has four kids, so you could say that each of her kids has one wolf-tempered dog as its pet. There's a reason why we jokingly call them the Starks, like the character from Game of Thrones.

One day when we've rented a cabin in the winter, two of the four Huskies took off into the night. A whole search party was formed to look for them and, in the end, when they got hungry, they came back on their own, with pretty much no outside prompting. And they were just 2 and 4 years old, too – so not old and experienced dogs by any stretch of imagination.

Now, new research into Siberian Huskies and Wolfdogs in general revealed that this behavior of our dogs wasn't that uncommon. Just like any Wolfdog, Siberian Huskies are equal amounts of fiercely loyal and ridiculously hard-headed. They can be lap dogs just as easily as they can be sleigh dogs – and it all comes from their wild origins.

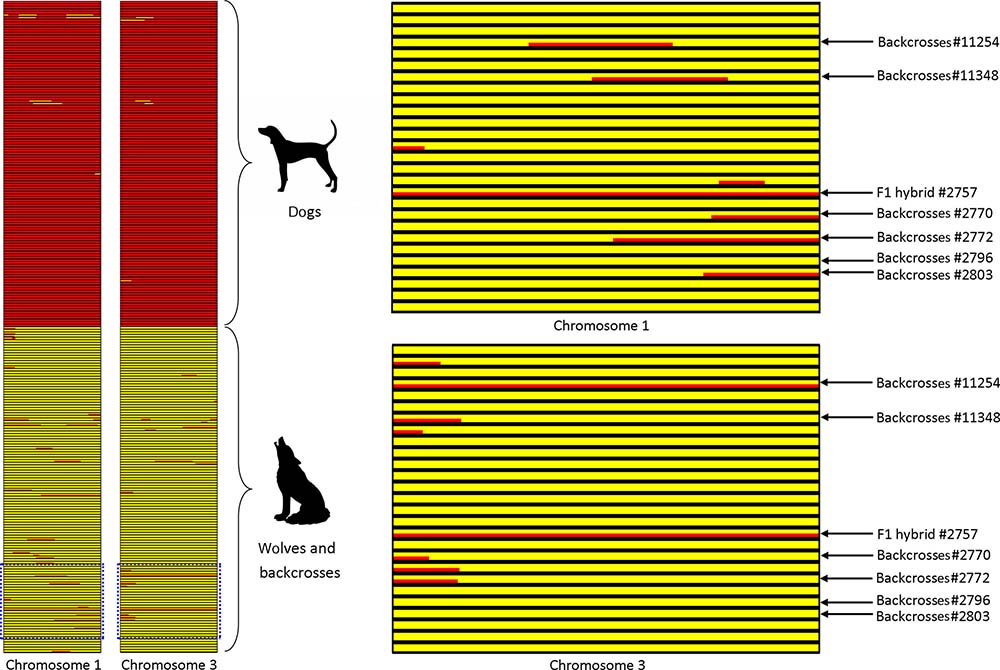

In fact, breeding between wolves and dogs goes both ways. This new study from the University of Lincoln in the UK has shown that the Eurasian grey wolf's gene pool has now been permanently marked by cross-breeding with domestic dogs, such as Huskies, Alsatians, Malamutes, etc. The study findings were published in Evolutionary Applications journal (full study paper here).

“A large number of wild wolves in Eurasia carry a small proportion of gene variants derived from dogs.”

It goes so far that researchers are now arguing that “genetically pure” wolves don't really exist anymore.

Years and years of cross-breeding has affected domestic dogs and taken its toll on the wolf genome, too.

RELATED: 25 Wolf Dog Breeds

The new study also sheds a new light on just how common cross-breeding between wolves and dogs has been throughout history. We probably could have gathered this ourselves, considering the amount of wolf-like domestic dogs that now exist. But there's a big difference between a dog with a wolf gene and a dog that has been manufactured to look like a wolf.

Markings maketh not the dog, and this is very much the case with wolves and dogs. Wolfdogs – such as my friend's Siberian Husky – have a proven genetic link with wolves. Other dogs may have similar markings to those of Wolfdogs, but they might just be a mix of other Wolfdog breeds, such as Alsatians, Malamutes, and Huskies.

The big difference though comes in the temperament. Manufactured Wolfdogs have been bred to be more suited to a domestic lifestyle. You can't mistake a real Wolfdog's temperament – they're hardheaded, vocal, high in energy and very anxious about being left alone.

What are the consequences of this for the Eurasian grey wolf?

The Eurasian grey wolf is what's known as a “keystone species” – its existence very much determines the viability of its habitat. Lack of regulation in the breeding of Wolfdogs, especially in Eastern and Northern Europe, is what has led the grey wolf into this situation in the first place. That's why the study shows that more control is needed over irregular hunting, small wolf packs, and roaming dogs.

“But I still want a Husky because they're pretty!” you or your friend might say.

“But I still want a Husky because they're pretty!” you or your friend might say.

That's fine, and, as long as the Husky has a clear heritage, you're safe to get one. But always make sure to research your pet's pedigree, because breeding some dogs causes a lot more damage to habitats and nature than you might think.

As for my friend's Siberian Huskies, they come from a long line that has been very well-documented, but you can see their wolfishness still. So, don't worry, you'll still be getting that taste of the wild, without having to destroy any habitats at all.

READ NEXT: Study Comparing Wolves and Dogs Explains Why Canines Are Our Best Friends

Study Reference:

- Adrián Castro-Insua, Carola Gómez-Rodríguez, Jens-Christian Svenning, Andrés Baselga. A new macroecological pattern: The latitudinal gradient in species range shape. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 2018; 27 (3): 357 DOI: 10.1111/geb.12702